WTT’s Salmo Trutta 2020: Jet Lag and Brook Trout

During these strange days of lockdown (in the course of which I’ve been temporarily furloughed from my Wild Trout Trust urban river role), we’ve all started adapting to new ways of working.

Formal meetings and family gatherings alike have moved onto digital platforms, where it’s likely that many of them will stay for the foreseeable future – and some of them maybe forever, saving lots of time, cost and carbon emissions on roads and public transport.

Other changes have been felt too, and this includes WTT’s decision to delay printing this year’s issue of the membership magazine Salmo Trutta until later in 2020, meanwhile publishing it online for the very first time.

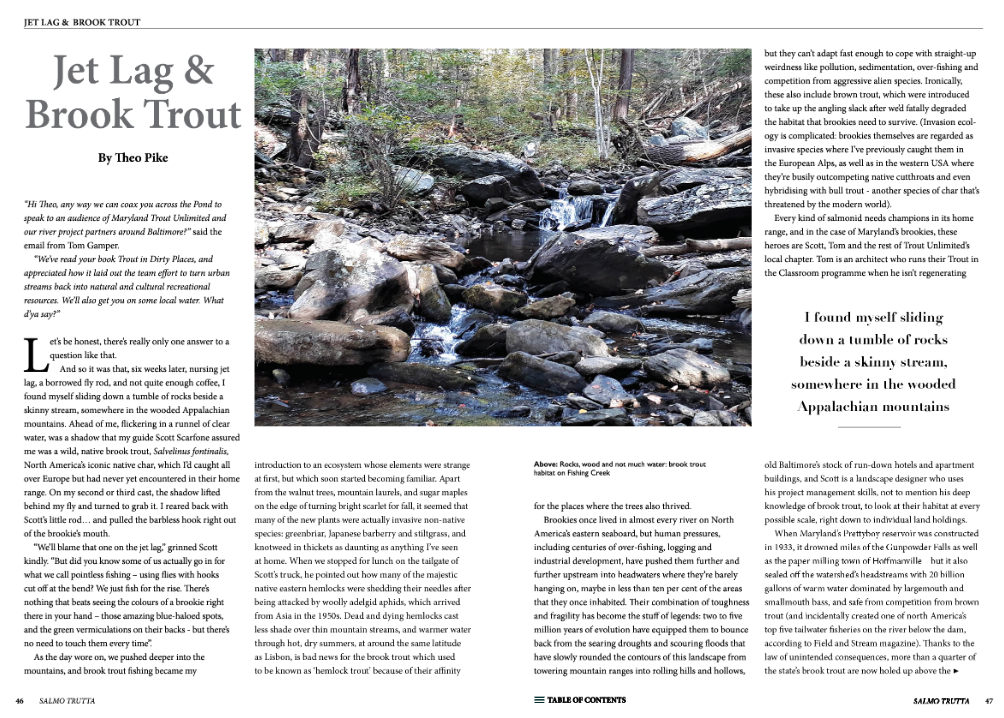

I’ve already written about my speaking trip to Maryland last September, here and on the WTT website. Now, thanks to Salmo’s editor Tim Jacklin, I’ve been able to go into more detail on some of these themes – getting to know the amazing Maryland chapter of Trout Unlimited, and exchanging knowledge and insights from our shared enthusiasm for restoring urban rivers as assets for their local communities. And, of course, the unrivalled experience of hunting wild, native brook trout with some of these guys in the Appalachian mountains:

True to form for urban river restorationists, we finally sniffed out a proper Dirty Place: a long double-barrelled culvert under a highway, where the shrunken creek ran thinly over a refrigerated concrete sill before sliding into the deepest pool we’d located all day. There, an astonishing shoal of twenty or thirty trout were facing downstream in an eddy scoured along one wall, where they kept their mouths zipped firmly shut in what we later decided must have been a pre-spawn sulk, pointedly ignoring an escalating sequence of midges, caddis, shrimps, and finally streamers (which I found the five-foot loaner rod lobbed into the head of the eddy with surprising efficiency).

Up on the bank, an ankle-twisting berm of rubble and slag from Civil War furnaces, I could hear Tom and Scott asking each other why they’d never fished this pool before, and arguing about the dark shape in the water that had to be a log. “It hasn’t moved since we got here… it’s way too big for a brookie!” Eventually, none of us could stand the suspense any longer, and I waded up slowly into the scour to see what was really in there. Small fish exploded in puffs of silt around my ankles, and the dark log resolved itself clearly into a brook trout no less than sixteen inches long, black as night apart from the diagnostic bright white edges on its fins.

Jet-lagged or not, that’s a real-life hallucination that will stay with me for years to come.

In many ways, this goodwill visit already feels like a relic from a previous age of innocence – it may be a very long time before many people feel able to squeeze themselves into sealed tubes flying between continents again – and a good thing, too, for the health of the planet. None of us can afford to emerge from lockdown and carry on doing everything exactly as we’ve always done it before, and this is a truth that applies equally to those of us who have already been rationing our travel carefully.

All this means that my personal mantra of Fish Where You Live feels even more like the way of the future. But I’ll always be grateful to have experienced how Maryland’s river restorationists fish where they live, in the course of this epic little trip of a lifetime.

Jet Lag and Brook Trout is published in the 2020 issue of Salmo Trutta on the WTT website: click here to read it (and much more!)

Leave a Reply