A new TWIST for the Sheppey?

As I’ve recently written in the Wild Trout Trust’s autumn newsletter, this is the kind of story that many of us know…

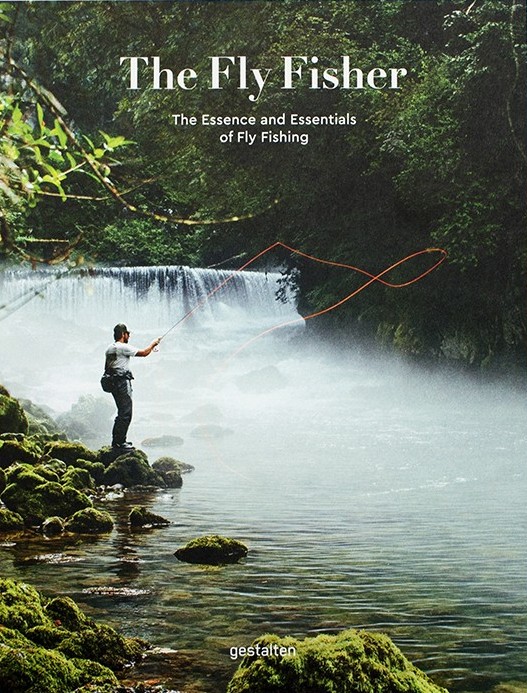

A spring, or a line of them, bubbling and gushing out of a rocky hillside. Tumbling downhill, meandering through an upland meadow where trout and bullheads dart above the gravel, and human huts are built beside the clear water. Then over and down the contours again, gathering force, carving a valley that curves and steepens before bursting out onto the plains and wetlands below.

Centuries pass, and the huts get bigger, growing into mills that tame the river’s flow. Quarrymen’s fire and dynamite shatter the faces of the gorge, gouging out freestone and rubble for the construction of dams, diversions, roads and even more buildings that loom over the river and turn its currents dark with pollution.

Eventually the mills fall derelict, and the water runs clear again. Here and there, the banks of the leats and millponds are tidied and gardened for the ornamental value they add to old mill houses and new loft apartments; more often, the river flows unnoticed except in times of flood, or unusually noxious discharge from one of the factories that still stand upstream. Sometimes a curious angler leans over a bridge and asks where the trout went: the authorities shrug and say “too many weirs, we’ll never get them back…”

This is a story that many of us do know well – and in this case it’s all about the River Sheppey.

Rising at St Aldhelm’s Well near Doulting, the Sheppey flows down from the Mendips to meet the main River Brue on the Somerset Levels through a pretty, winding limestone valley that often reminds me of somewhere in Slovenia.

The area’s long history of cloth and cider milling has left a complicated legacy, including at least 35 weirs and other barriers to fish passage; channel simplification and straightening, to deliver a smooth and consistent flow of water to the mills, and make room for the road down the valley, have also steepened the gradient of the river and shortened the length of its channel. Most of the river’s course through Shepton Mallet was built over by pre-Victorian developers, and now, when heavy rainfall and runoff overcharge the old culverts (such as during Storm Alex in October 2020), modern residents sometimes find the Sheppey coming up to see them through their floors. Pollution has always been a nagging problem – most recently when something knocked out the sewage works between Shepton and Croscombe in August 2019, and caused a 15km fish kill that reached all the way out into the Somerset Levels. Local people were outraged, and we’re still waiting for the results of the EA’s investigation, and maybe an eventual prosecution.

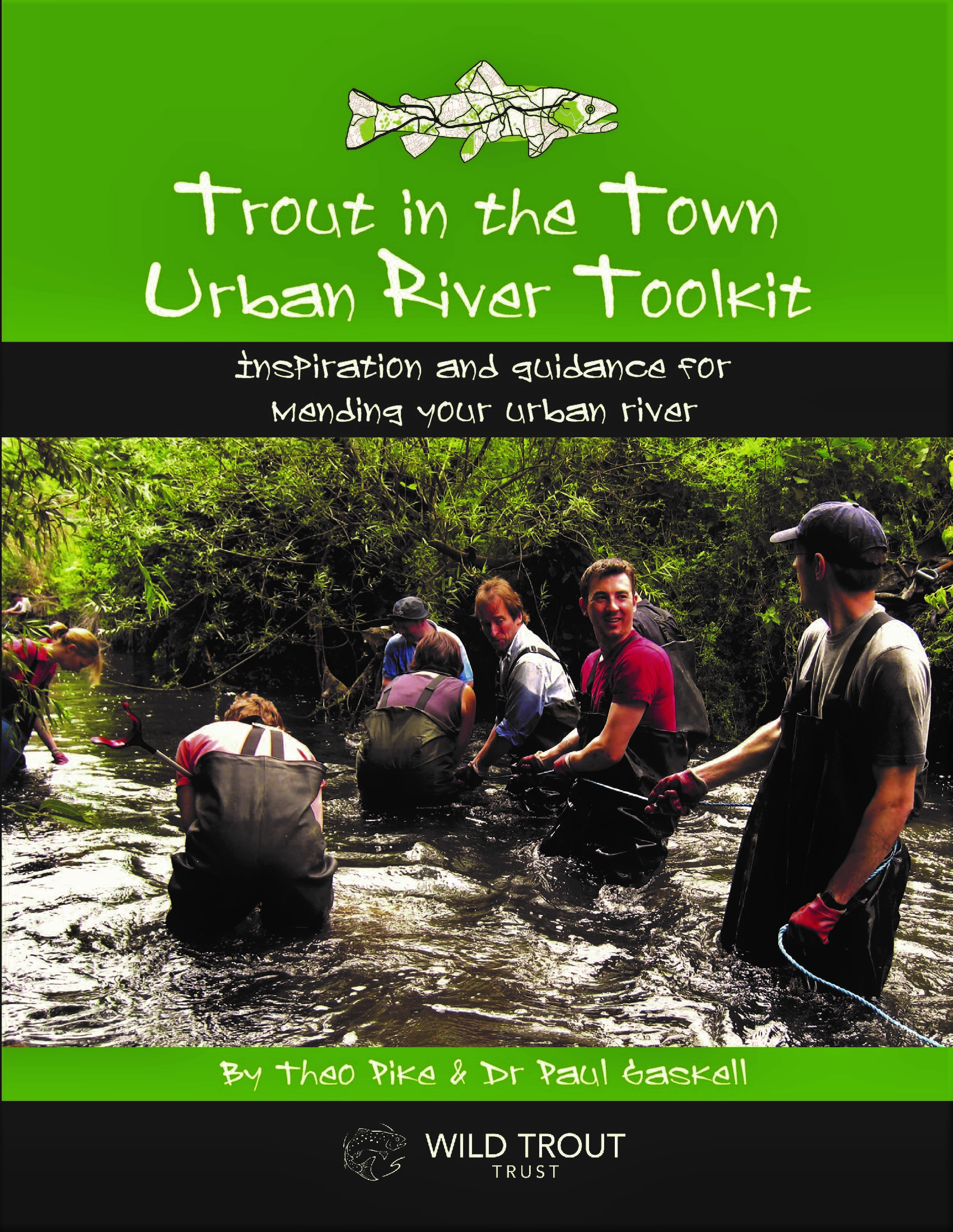

If you think all this sounds like perfect territory for a Trout in the Town project, you’re right. Thanks to some well-timed funding from the EA and Somerset Catchment Partnership for the new TWIST (Transforming Waterways in Somerset Towns) project, I spent several weeks last winter assessing the urban reaches of the Sheppey and Axe catchments, documenting the results in a suite of reports, and starting to recruit local people as riverfly monitors to keep an informed eye on areas where no current data seems to exist at all.

Trained in July this year, these keen volunteers have already started to produce some interesting findings (including, too late for the WTT newsletter, at least 5 different point sources of pollution in the Shepton Mallet area, which the Environment Agency and Wessex Water have been duly investigating). And all this revival of interest in the Sheppey has led to a new project partnership of the EA, WTT, FWAG, Westcountry Rivers Trust and Mendip District Council’s flood consultants, to focus on the river’s multiple challenges.

A recent site meeting with the owner of one of the valley’s redundant weirs suggests that we’ve already found a possibility for restoring fish passage whilst also protecting vulnerable infrastructure. After that, with useful lengths of habitat properly reconnected, we might even be able to talk about translocating a new population of wild trout into this area – crucially, well upstream from the constant threat of Shepton Mallet’s sewage works.

After such a lot of twists and turns, can we dare to dream of a happy ending for the Sheppey’s story?

We’ve only just started writing this new chapter for the river… but yes, maybe I think we can…

Leave a Reply